Medieval Jugs

A journey of discovery

My early encounters with ceramics come from an early age. I had always been interested in art, it was my best subject at school along with maths/science.

In the village where I lived as a child there were the remains of a moated 13th century manor or farm house and I would spend a lot of my spare time with the local archaeological society team excavating the place. I was struck by the difference in the pottery I was finding to modern day pottery. Of course it was the fact that it was quality handmade pottery with all its wonderful non-standardisation and nice thumbed handles etc, compared to the industrially made pottery that I was used to at home. I didn’t really consider that it was possible to make that type of pottery, as I thought it was just something from the past.

On leaving school I embarked on an apprenticeship following in my father’s footsteps as an electrical engineer. Part of my apprenticeship was a day release course at the local college for the academic side of the apprenticeship. At the college I discovered there was an art department with a small pottery section run by Joanna Constantinidis, so I started spending lunchtimes there playing with clay. I began to realise that you could actually make ‘handmade pots’ .

However after 3 years into the apprenticeship I took the brave move of leaving luckily with my parents’ support, and going to Art College full time. I did a pre-diploma or foundation course where I studied all aspects of art, including, painting, sculpture, ceramics, photography, printmaking, .

Applying for a Diploma in Art and Design course brought me up to Newcastle upon Tyne in 1970 where I studied Ceramics full time. After leaving college I worked in teaching at Beamish Museum and also set up my own pottery studio in Cails Yard, Haymarket, in Newcastle. Then in 1983 I was offered a job running a government funded MSC project to renovate a group of derelict 17th -19th century buildings and to turn them into an arts centre. I was in charge of the Arts team to make all the decorative features, hand-made ceramic tiled floors, wall mosaics, roof Finials, etc. I employed 12 people/artists to work with me for the 5 years the project ran.

The building site itself was in a terrible state; workmen had been there before I arrived and were clearing all the 20th century structures that covered in an old courtyard to reveal the earlier buildings that needed a lot preserving. I was aware that the location of this half acre site was within the old town walls and on the supposed line of Hadrian’s Wall. So I kept an eye out, and the first thing I found under some floor boards right on the ground surface were fragments of Roman and Mediaeval pottery, which immediately got my interest.

Then I spotted that the site workmen digging a drain trench had thrown a load of Roman and Medieval pottery into the skip outside. I recovered all the pieces of pots from the skip, much to their amusement. I then decided to take a serious approach and asked the site director if I could cut a proper study trench. He reluctantly allowed me to do this, worrying I would hold up the work in hand (in those days there was no automatic right to allow an archaeological inspection of a site). I cut a trench and found the foundations of what turned out to be a Roman Milecastle (see the Roman page).

From then on I supervised all the diggings on site and the site workmen kept me informed of finds. By then, I had a full team of artists employed on the arts projects and got them to help me in the excavations. And the work was recorded by the City Archeologist Barbara Harbottle. We even used the clay we dug up to make some of the tiles for the floors for the Art Centre project.

I was on paternity leave for a couple of weeks with the birth of my son, when I got a phone call to come in immediately. The workmen had scraped the top of a well and it was full to the top with pots from the 14th century. We actually found 4 wells in all but this was the best one. As carefully as time would allow, I emptied the well.

So it seemed my early interest in ceramics and Mediaeval archaeology came round in a full circle and allowed me to recognise and save these finds which would otherwise have been lost for good. And my ceramics team even managed to design, make and lay a few thousand sq. feet of wonderful tiles, despite all the time spent digging in the courtyard! -see the Tile Project.

The Jugs

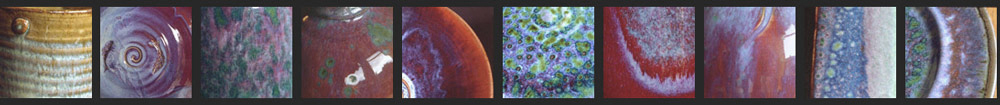

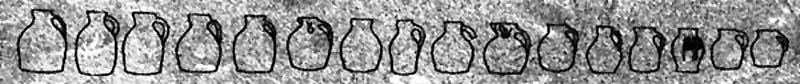

All the ceramic vessels that came out of the well were Jugs. There were about 16 more or less complete ones, and the remains of about another 40. The Well also contained pieces of wood platters and shoes. All the jugs had a “saggy base” as a common feature, this is a rounded base so that if they were sat on a flat surface, they would wobble considerably. The city archaeologists I reported back to, they made a great job of surveying the site and cataloguing all my finds. From their archaeological experience, they thought that the rounded bases were the result of either the way the pots were fired, or the way they were lifted off the wheel when the clay was wet, either way, they thought the saggy bottom was not intentional, however I thought otherwise.

Mediaeval kilns of that date did not use ‘kiln shelves’ or ‘saggers’, but the pots were stacked literally up on top of one another to the top of the kiln maybe 10 or more jugs high. Galena or white lead powder for a glaze of sorts was dusted onto the pots when the clay was still wet(bad for the potters but actually okay for consumers as the lead coating was only on the outside of the vessels) and ‘once fired’ up to a temperature of probably around 1100ºC, enough for a reduction atmosphere to have an effect. A lot of the jugs had ‘scar’ marks on their tops and bases from the adjacent jug in the stack.

I studied with a potter’s eye all the complete jugs and all the parts/pieces of bases of the others. I concluded that the bases were deliberately made rounded, as on close study I could see fist and hand impressions where the bases were definitely pushed out into a rounded shape and then fettled/ knifed into rounded almost egg-shaped vessels . Also looking by studying cross sessions of broken bases, I could see that some of the bases were made first then coiled/ thrown up on a potter’s wheel, and thrown up fairly thin, being fettled down to shape only on the lower part and base.

The jugs themselves were made of a fairly coarse clay but were very light in weight for their size, balanced and handled well and strong, so strong that in fact for one of them, I was standing on when I excavated it! (not intentionally). It’s the ‘egg’ principle – a rounded end means a very strong structure, that also would help in the stacking and stability within the kiln

The rounded bases of the jugs gave strength and thermal resistance to the pottery vessels and they would be set into hot ashes in the hearth to cook soup or warm/mull your beer (they liked it warm in those days). Also when a jug with a rounded base was sat upon a table you could pour from it, without the need to lift it, you simply rolled it enough to pour from it.

These vessels were meant for everyday use, a multi-purpose domestic vessel for storage, on the table or cooking in, for kitchen or public house; the wealthier people would probably have used metal instead for table use. I also found in the Well remains of wooden platters so these would have been for serving up food on. I also found large numbers of Cattle horns which were ‘stripped horns’ where the outer layer had been stripped off to make drinking vessels. Also I found in the Well many parts of leather shoes preserved in the anaerobic condition of the Well. So it is possible that I had found the rubbish tip of an ale house. The well itself was not very deep, about 20 foot, so my guess is that it had dried up and was used as a tip instead. I do not know why complete pots were discarded, but at about this time there was an outbreak of the plague in Newcastle in which a large percentage of the population perished, so the houses and household items were simply abandoned as the people who could moved out of the town to avoid it. The Medieval houses that had stood there would have been the houses of the ‘well to do’ town’s people as they were higher up the bank in the top part of the walled town near the West Gate, well away from the river and all its smells . The houses had orchards/gardens and their own wells! I found 4 wells in all, one producing all the jugs.

The jugs were beautifully made with a lot of individuality and enjoyment in the making. Thinly potted and light for their size. I found one which I guess was more of an apprentice piece or a “end of week” piece, It had a lot of surface decoration and a thumbing around its base. It was assumed that the thumbing of the base of some jugs from that date was intended to counteract the sagginess of the bases so as to stabilise them. I don’t think this is the case, as this one still rocked/rolled on a flat surface, so I assume it’s a decorative feature. Many had beautiful strong handles with great individual thumbing; it’s great to see this and to be able to relate to these potters of 600 years ago, with their thumb and finger prints still fresh in the clay. Some of the jugs had ‘pot stamps’ (impressions/designs) into the clay. I’ve re-made these pot stamps and I use them in my own work now, with my own interpretations of the stamps.

What I love is that they were all made with the great integrity of artists and craftsmen, and with individuality, despite being intended as utilitarian vessels. They were wonderful pieces, and it was a privilege to find them.

A note on the photos: all these photos were scanned in from slides I took at the time of discovery so some of the quality is not the best. Also most of the jugs were only partially assembled, and were kept loosely together with brown paper and tape as can be seen, so they can be taken apart again for further study. Hopefully they will be fully researched and restored in the future and I will re-photograph them.

David Fry 1999

Click on individual pictures for full size.