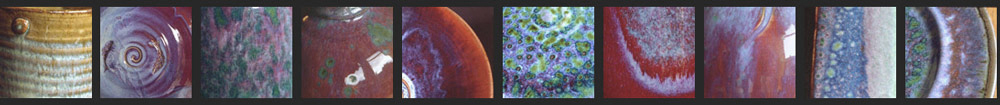

Oriental Mystery

Reproduced from Ceramic Review No.167 – 1997

The Jun Glaze

David Fry has been involved in ceramics for over thirty years, studying at various colleges, including Newcastle Polytechnic. After holding several teaching posts, in 1983 he was offered the job of supervising production of the architectural ceramics for the new Arts Centre in Newcastle, where he now bases himself, concentrating today on producing a range of hand-thrown work, much of it inspired by early Chinese and English Medieval pottery. David Fry has carried out extensive research into Chinese glazes and now uses this as a base for the unique range of glazes he has formulated for his ceramics. Here he outlines his quest for a classic Jun glaze.

Some time ago a London collector of Chinese ceramics, wrote to me, a sad letter, saying that his favourite piece of porcelain, a Junware (or Chun) dish of the Sung Dynasty, after being looked after for nearly a thousand years, had been broken into a ‘thousand’ pieces when dropped by his cleaning lady.

He had noticed the similarity of my work to the early Chinese pots and having purchased pieces of mine was given my address by the gallery. He asked me if I would make a copy of the broken piece. I agreed as this seemed a great opportunity to study Junware close up. I have long admired and loved these early Chinese works and often go to Durham University to look at its excellent collection. This was a chance to study the broken pieces close up in cross section, sent to me by the collector.

The profile of the dish was worked out from assembling some of the pieces. The clay body fabric I worked out fairly quickly as it was similar to a clay I use. I then started to study the Jun glaze, a thick, beautiful, opalescent pale blue, the surface fairly shiny but not runny. The glazes I have developed for my own work are based on copper and iron mixtures and are more like the green/blue and red Flambé glazes of the 17th and 18th centuries rather than the Jun glaze of the 11th century. Working out the Jun glaze proved much more difficult.

From reading articles about the glaze I gathered that the illusive blue comes from the effect of light hitting the glaze and not from the presence of pigment. However, I found this not to be the case. Iron, I discovered, was an essential ingredient to give the blue coupled with phosphorus, coupled with the firing method. I can only assume that glaze recipes not using iron were fired over a high iron rich body, with the iron leaching into the glaze. The clay body I used is low in iron, porcelainous in nature. When broken the cross-section colour was as the original, grey with a fine white line between the glaze layer and the grey body.

I started with the classic 4-3-2-1 recipe and spent about a year putting a few tests in every glaze firing, finally coming up with a recipe that worked with my firing technique. For the phosphorus content I used wood ash, which gives an intimate combination with Calcium, and other trace elements.

My kiln, my own design, is fired mainly with natural gas. It has a single burner feeding in along the lower front with the flue outlet at the lower back. For glaze firing I use the burner on the natural draught I get from the 50ft. chimney. The single burner gives interesting results in my glazes with vivid flame marks, some pieces part oxidized, part reduced, some strongly reduced and a few with beautiful crystalline effects – all in a single firing.

The Jun glaze only worked in one spot in the kiln, and this was in the hottest and most reduced corner, opposite the burner on the lower front. Early on in my firings I stoke wood into the kiln to increase the reduction/smokey atmosphere in the kiln. The temperature in the centre of the kiln is about 1350°C with the hottest spot being somewhat more, which takes about 24 hours to reach, with the last three hours firing fairly oxidized. I then shut off, clamp it up and cool for 48 hours before opening. This firing techniques achieves the colours I seek and although it is not the same as the early Chinese methods, it is close. The Chinese firings took much longer and cooled slower. With my Jun glaze, the colour is exactly the right blue with it thinning to a golden tone on the rim of the dish. However, the bubbles within the glaze layer are larger in my piece compared to the original. There is no doubt due to the originals longer firing.

In summary I found this jun glaze relied on two main factors – the critical balance in the glaze mix between iron and phosphorus and, secondly’, the firing technique. It only worked in the hotspot of my kiln where I also get my best ‘copper reds’. Interestingly, firing the Jun ware next to the copper reds I occasionally got the purplish/red flashing that is sometimes seen on ancient wares.

The Jun recipe I finally arrived at is:

‘real’ Potash Feldspar 45. Quartz 25. Whiting 17. Clay 9. Dolomite 2. Bone Ash 2. Iron Oxide 1.

I mainly use two different clay bodies, both made up by Peter Stokes of Commercial Clay in Cobridge, Stoke. He makes the clay up to my requirements of softness and grog content. One he calls ‘Plastic Throwing Clay’ which consists of Ball clay 50%, China clay 25% and Fireclay 25%, plus fine molochite 10%. The other I use for a lighter background to my glazes is called ‘Superwhite’ which consists of Ball clay 70% and Molochite 30%. For the Junware, I found mixing these two clay bodies 50/50 gave me a very good match to the original .I broke a test piece and in cross-section it gave the light grey body fabric with the fine white line between the body and glaze layer, and on the outside the unglazed area was a nice toasted tan oxidized tone, as in the original broken Jun.

To be classed as a ‘Potash’ feldspar the K2O content (by % weight) must be at least 4 times that of the other fluxes. Cookson’s is actually 12.2% K2O to 2.4% Na2O. Now my old rich blues are singing well again. I now get all my raw materials from Cooksons, however, they only supply them in 50 kilo bags which could be a problem for smaller scale potters.

Alternative recipes for Jun type glazes.

The Wollastonite glaze is slightly stiffer and not so Blue.

The Wood Ash glaze gives a pale green Celadon where thin, and a nice Jun blue where thick and pooled, it is also more runny. The Wood Ash(unwashed) I collect from a local farm are burnt hedge cuttings, mainly wild rose and hawthorn.

Potash Feldspar 40. Quartz 26. Clay 10. Wolastonite 22. Wood Ash 20. Iron Oxide 1.